We Don’t Experience the Same Reality

Two people can leave the same conversation carrying entirely different realities.

One feels understood. The other feels dismissed.

The same words were spoken. The same moment occurred. But the experience was not shared.

We often assume we live inside a common world, that events happen, and we all perceive them roughly the same way. Yet most misunderstandings come from the opposite being true. We do not share experiences. We only share situations.

What we call reality is filtered through memory, expectation, mood, and personal history. The moment reaches us, but it does not arrive untouched.

Philosophers have long tried to describe this. Martin Heidegger used the term Dasein — “being there” — to suggest that human life is not simply existing in a world, but existing as someone inside it. We do not stand outside experience and observe it. We participate in shaping it as it happens.

That is why the same day can feel meaningful to one person and empty to another.

Why does advice that feels helpful to one feel intrusive to someone else?

Why does even our past change depending on when we remember it?

Most conflict grows from forgetting this.

We treat our interpretation as the event itself. We assume disagreement means distortion rather than difference.

But if experience is personal before it is shared, understanding becomes less about proving and more about listening. Not listening for agreement, but listening for perspective.

Perhaps subjectivity is not a flaw in how we see the world.

It is the condition that allows each of us to live in it.

The Universal Language of Story

Some books travel further than their authors ever imagined.

The Bible has been translated into more than 3,000 languages.

The Little Prince into over 300.

Pinocchio into more than 250.

The Harry Potter series into over 80.

These numbers are impressive. But what makes them meaningful is not scale. It is reach.

A story that crosses language crosses interpretation. It enters cultures shaped by different histories, beliefs, and assumptions. Yet something within it resonates.

Why?

Because story precedes language.

Before we translate words, we recognize experience — loss, wonder, courage, doubt, love. The details may shift across cultures, but the emotional architecture remains.

When a book survives translation, it proves something quiet but powerful: meaning is portable.

And perhaps that is why books endure long after trends fade. They carry not just information, but reflection. They allow us to see our lives through another lens, then return to our own with greater clarity.

Translation does more than spread a story.

It reminds us that what shapes us is often shared.

From Shakespeare to BookTok: How Stories Travel Across Time

William Shakespeare and Agatha Christie have each sold an estimated two billion copies of their works. They lived centuries apart. They wrote in different genres. Yet their stories persist.

Today, books travel differently.

A viral video on BookTok can revive a forgotten novel overnight. A short clip can introduce millions of readers to a story published decades earlier.

The medium changes.

The mechanism remains the same.

Stories move because they resonate.

Shakespeare endured because his characters wrestled with ambition, jealousy, doubt, and love. Christie endures because mystery satisfies our desire for order and revelation. BookTok thrives because readers want to share the experience of being moved.

What we are witnessing is not a replacement of tradition. It is continuation.

From stage to print to algorithm, stories have always found ways to travel.

The question is not how they spread.

The question is why we still need them.

Because every era, no matter how technologically advanced, still asks the same human questions.

Who am I? What matters? How do I make sense of this moment?

Books do not answer these questions permanently.

But they help us refine how we ask them.

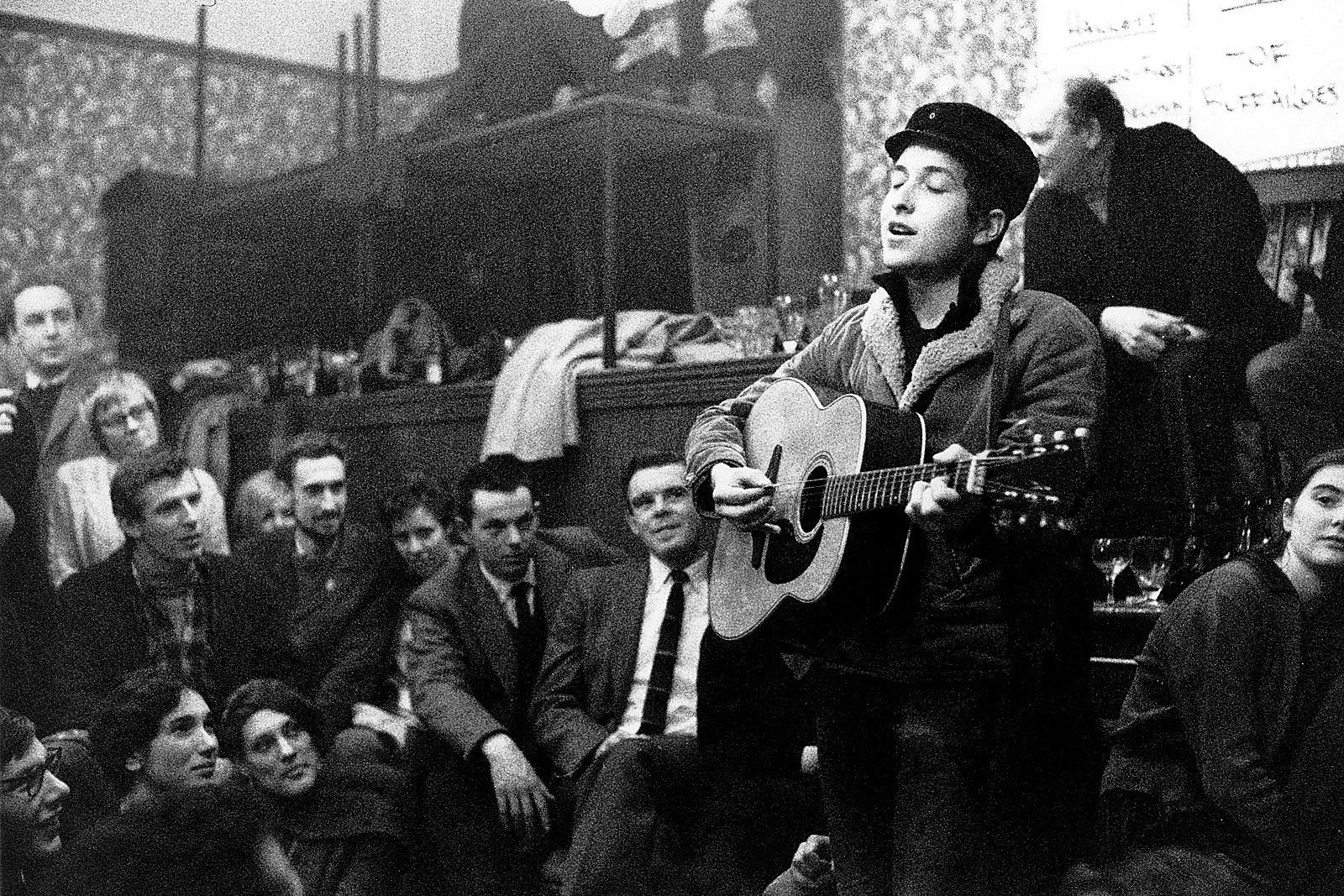

Is a Song Literature?

“Blowin’ in the Wind” by Bob Dylan is often described as a protest song. It raises questions about war, peace, freedom, and human dignity. But beneath its historical role lies a more enduring question:

Is it literature?

Songs and poems share a common lineage. Both rely on rhythm and repetition. Both use sound to carry meaning. Both are shaped to linger—long after the moment of hearing has passed. We often privilege poetry as “literary” because it exists on the page, but language does not lose its depth when it is voiced rather than printed.

That boundary blurred publicly in 2016, when Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for creating “new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” The decision unsettled traditional definitions, but it also clarified something essential: literature is not confined to form.

As Harper’s Magazine observed at the time, the literary includes not only what is written, but what is expressed and invented—language that departs from ordinary usage to reveal something human, reflective, and lasting.

Written in 1962, “Blowin’ in the Wind” became an anthem for civil rights and anti-war movements not because it delivered conclusions, but because it refused to. The song offers a sequence of unanswered questions, returning again and again to the same refrain.

How many roads must a man walk down

Before you call him a man?

How many years can some people exist

Before they’re allowed to be free?

How many deaths will it take ’til he knows

That too many people have died?

These lines endure because they do not resolve themselves. They invite reflection rather than agreement. The listener becomes part of the meaning.

If literature helps us notice what we already sense but struggle to articulate, then the question is not whether this song qualifies.

The question is whether we are willing to listen long enough for its meaning to take hold.

Light, Rhythm, and Meaning in “The Hill We Climb”

Thoughts and Reflection

What makes the words of Amanda Gorman so meaningful is not just what she says, but how she leads us there.

Her conclusions grow naturally out of recollection. Each image builds on the last, guiding the listener forward rather than confronting them outright. When her words rhyme, they don’t decorate the poem — they land directly on the truth being expressed. The rhythm reinforces the message instead of distracting from it.

Her approach is calm, even gentle, yet the ideas themselves are bold and challenging. She doesn’t raise her voice to demand attention. She invites reflection, and that reflection carries weight.

There is light in her language, even when she speaks about darkness. Not in a naïve way, but in a hopeful one. Like a breath of fresh air in a heavy room, her words remind us that struggle and possibility can exist side by side.

That balance, between grace and urgency, memory and movement, softness and strength, is what gives her poetry its lasting power.

Her poetry doesn’t shout at the world. It changes it quietly — one image, one truth, one breath at a time.

Aeschylus was quoted by Robert Kennedy at Martin Luther King, Jr's death

“What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black.”

The quote appears in Robert F. Kennedy’s impromptu speech delivered in Indianapolis, Indiana, on the evening of April 4, 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (JFK Library and Museum, and The Library of Congress)

In the John F. Kennedy Library’s archive, it’s part of his “Statement on Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Indianapolis, Indiana, April 4, 1968.” JFK Library and Museum

The full line is included in published transcripts such as Voices of Democracy under “Kennedy Speech Text Rally in Indianapolis.” Voices of Democracy

Wikipedia also cites it in its article on “Robert F. Kennedy’s speech on the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.” as one of his best known lines.

“Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget

falls drop by drop upon the heart,

until, in our own despair,

against our will,

comes wisdom

through the awful grace of God.”

Thoughts about this Poem

Robert F. Kennedy also quoted these lines from the poem in his impromptu speech announcing the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. That moment—raw, unrehearsed, and spoken from the heart—remains one of the most powerful examples of public grief met with quiet strength.

The same lines were later inscribed on Kennedy’s tombstone at Arlington National Cemetery. He once said, “My favorite poet was Aeschylus.” In turning to poetry during one of the nation’s darkest moments, Kennedy reminded us that words—even ancient ones—can still speak into the present.

About Aeschylus

Few reliable sources exist for the life of Aeschylus. He was born around 525 BCE in Eleusis, a town northwest of Athens. As a young man, he worked in a vineyard until, according to tradition, the god Dionysus appeared to him in a dream and inspired him to write for the stage.

At just 26, Aeschylus had his first play performed (499 BCE). Fifteen years later, he won his first prize at the Dionysia festival, Athens’ most prestigious playwriting competition. Often regarded as the father of tragedy, Aeschylus wrote with a depth and weight that transcends centuries. The lines Kennedy quoted come from one of his surviving works, Agamemnon—a meditation on suffering, wisdom, and the human condition.

Why These Lines Still Matter

In moments of loss, words often fail. But sometimes, they also hold us. The fact that a 2,000-year-old line could resonate with the grief of 1968—and still echo today—speaks to poetry’s enduring role: not to solve pain, but to give it shape.

Originally published in 2022. Revised and relocated.

Fire and Ice: Why Frost’s Shortest Poem Still Feels Unsettling

With just nine lines, Robert Frost reduces the end of the world to two human impulses—desire and hate, heat and cold, fire and ice.

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice. From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To know that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

What makes Fire and Ice endure isn’t its warning, but its refusal to resolve the tension it introduces. Frost doesn’t argue for one force over the other. He suggests that either would suffice.

That quiet equivalence is what lingers.

Fire is often read as passion—desire, ambition, intensity. It burns quickly and visibly. Ice, by contrast, is slower. It hardens. It withdraws. It preserves resentment rather than releasing it. Both destroy, but in different ways.

What the poem leaves us to consider is not which force is worse, but which one we are more familiar with.

Over time, readers tend to map these forces onto lived experience. Some people burn hot—reactive, driven, emotionally charged. Others grow cold—distant, withholding, resolved in their certainty. Neither posture feels harmless when sustained. Surrounded by one extreme, relationships suffer. Balance disappears.

The poem’s power comes from how easily it shifts from cosmic speculation to personal recognition. The “world” Frost describes doesn’t have to be the planet. It can just as easily be a marriage, a friendship, a workplace, or an inner life.

There is also a quieter literary echo beneath the surface. In Inferno, sinners are punished in both fire and ice. Passion and betrayal receive equal weight. Frost doesn’t cite this directly, but the parallel deepens the poem’s moral ambiguity. Destruction doesn’t require spectacle. It only requires persistence.

What Fire and Ice ultimately resists is certainty. Frost doesn’t claim to know how the world ends. He only admits that he has “tasted of desire” and knows “enough about hate.” That modesty—paired with clarity—is why the poem continues to surface whenever we think about extremes.

The poem survives because it doesn’t tell us what to fear.

It asks us to notice what we tend toward.

And to consider the cost of staying there too long.

This reflection is part of Literature & Meaning, a series on how enduring works continue to shape interpretation over time.

Why Certain Lines Refuse to Leave Us

Some lines stay with us long after we’ve forgotten the plot that carried them.

We may not remember when we first encountered them, or why they appeared at just that moment, but they linger. They resurface years later in conversations, classrooms, essays, or quiet thoughts. Not because they are clever, but because they name something we recognize in ourselves.

This section begins with a simple question: why do certain lines endure?

Literature doesn’t persist because it offers answers. It lasts because it creates space for meaning, space we return to as our lives change.

A line that once felt abstract can become painfully clear years later. Another that once felt definitive may loosen with time. The words don’t change. We do.

This is where meaning lives, not in explanation, but in recognition.

When we return to literature, we aren’t looking for instruction. We’re looking for ourselves, older, changed, more complicated than we were before. A familiar line becomes unfamiliar again. Or suddenly precise. Or quietly unsettling.

That shift isn’t a failure of interpretation. It’s evidence that interpretation is alive.

When William Faulkner wrote, “My mother is a fish,” he wasn’t offering clarity. He was naming a fracture, how language strains under grief, memory, and identity. The line unsettles because it refuses to explain itself. It leaves room for the reader to feel what cannot be resolved.

When Aeschylus wrote that wisdom comes through suffering, he wasn’t making a promise. He was acknowledging a pattern, one that readers have recognized across centuries, cultures, and personal histories. The words endure not because they comfort us, but because they remain true in ways we continue to test.

These lines persist because they meet us where certainty fails.

Literature doesn’t tell us what to think. It reminds us what it feels like to think.

Literature & Meaning is a place to pause with words that have endured, not to resolve them, but to sit with what they continue to stir.

“My Mother Is a Fish”: Why Faulkner’s Most Peculiar Line Still Resonates →

There are lines in literature that stay with us not because they are elegant, but because they are unsettling. William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying gives us one of the strangest and most unforgettable: Vardaman’s declaration, “My mother is a fish.”

It’s an odd sentence—five simple words, childlike in structure, and yet heavy with meaning. For decades, it has puzzled readers, inspired essays, and filled search bars. But what keeps this line alive isn’t just its peculiarity. It’s the way it exposes something deeply human: the struggle to make sense of loss when our language hasn’t caught up to our experience.

A Child’s Logic Inside a World That Has Broken Open

Vardaman’s reasoning is literal. A fish becomes something else once it is cut apart; his mother, once alive, is now transformed into something not-mother. His world has shifted, and he reaches for the only framework he understands.

Faulkner wasn’t simply being clever here. He was showing us how children meet grief with raw logic. When the world becomes unrecognizable, they reach for metaphors they don’t yet know are metaphors.

Adults do this too—we just hide it better.

Identity, Change, and the Names We Give to Loss

There’s a deeper truth at the center of Vardaman’s confusion:

When someone changes in a way we cannot comprehend, we scramble for new language to match the new reality.

We feel this when:

a relationship fractures

a loved one becomes someone we hardly recognize

illness changes a person’s mind, personality, or presence

death reshapes our understanding of who they were

We often respond with the emotional equivalent of Vardaman’s line.

We rename the experience to survive it.

“My mother is gone.”

“The person I knew isn’t here anymore.”

“He’s not himself.”

“It doesn’t feel real.”

Language becomes a coping mechanism—imperfect, blunt, necessary.

Where Logic Fails, Metaphor Steps In

Faulkner understood something essential about human nature:

We use symbols when reality feels unmanageable.

When Vardaman says his mother is a fish, he isn’t offering a literal explanation.

He’s reaching for the only metaphor he has.

Adults do the same when we say things like:

“My life is in pieces.”

“Everything is up in the air.”

“I’m trying to keep my head above water.”

We tell stories to understand ourselves, even when the stories are strange.

Why This Line Still Matters Today

What makes “My mother is a fish” timeless is not the shock value.

It’s the honesty.

It captures:

the collapse of certainty

the reshaping of identity

the struggle to name what can’t be named

the way grief pulls language apart and forces it back together

It reminds us that confusion is not a failure of understanding—it is part of the process of making sense of what has changed.

Sometimes truth arrives through the simplest, strangest sentence.

Closing Reflection

Faulkner wasn’t writing about a fish.

He was writing about the fragile bridge between what we know and what we can no longer explain.

When life changes suddenly—when someone we love becomes someone we lose—we reach for words that are too small for the moment. And yet, sometimes those words are all we have.

Vardaman’s line stays with us because it exposes a reality we don’t often admit:

Grief makes children of us all.

Related Reading

If you're interested in the original context and symbolism behind Vardaman’s line, you can read my earlier 2018 analysis of As I Lay Dying here:

Related Reading

If you're interested in the original context and symbolism behind Vardaman’s line, you can read my earlier 2018 analysis of As I Lay Dying here: