When an Image Outlasts the Moment

Photo by Jeff Widener / Associated Press

Some images don’t belong to a single moment in time. They belong to memory.

In an age of constant images—most of them fleeting—it’s easy to forget that a photograph can still think for us. It can hold meaning without explanation. It can endure without commentary.

One of the clearest examples is a photograph taken in Beijing in June 1989, captured by Jeff Widener. A lone man stands in front of a column of tanks. We don’t know his name. We don’t know his fate. And yet the image continues to speak—about vulnerability, resistance, and the quiet force of presence.

The photograph hasn’t aged because its meaning was never tied to a headline. It was tied to a human moment.

This is what visual essays remind us: sometimes the image is the essay.

Originally published in 2020: The Photo Is the Essay

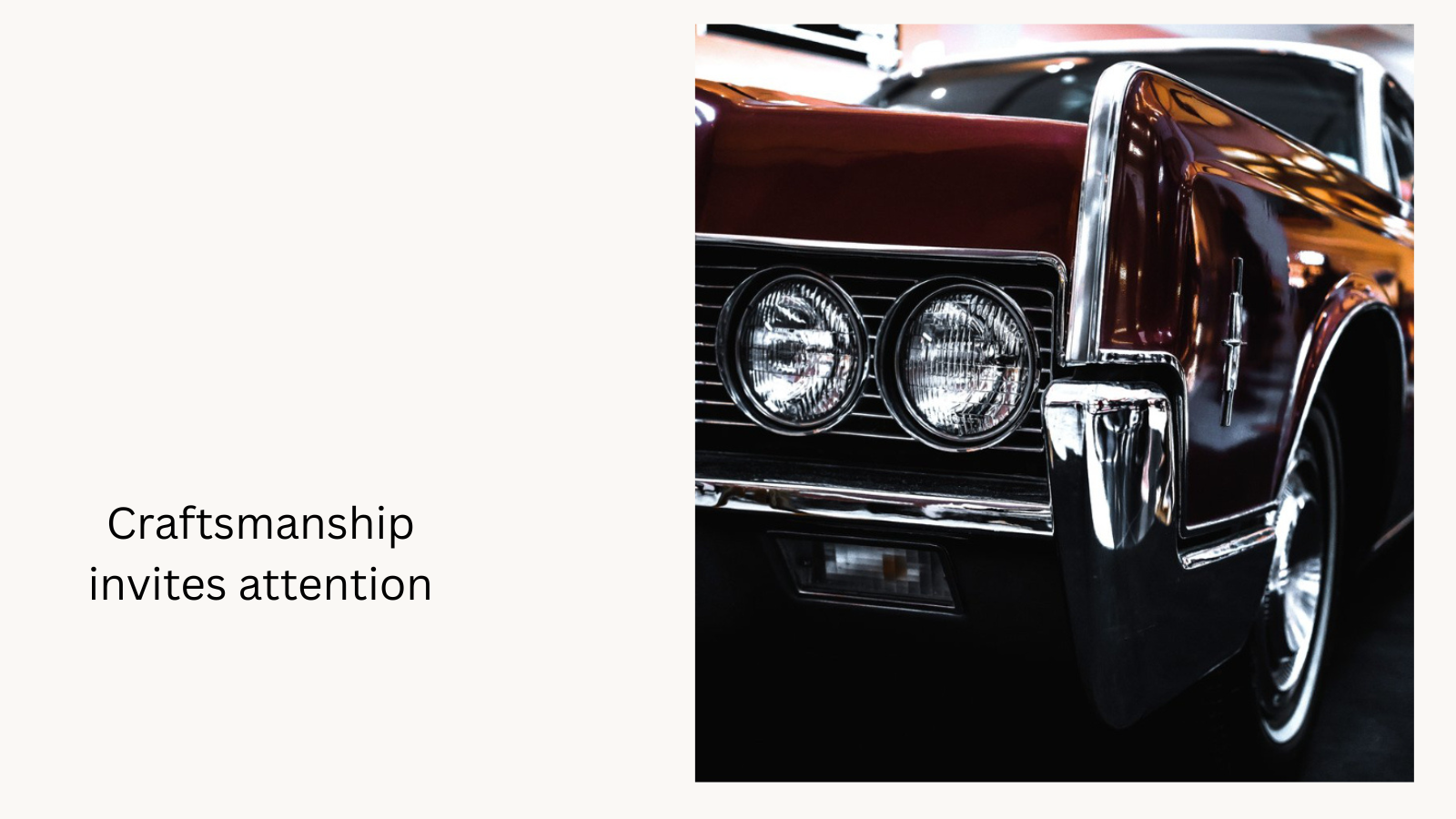

Old Stuff Inspires: When Craftsmanship Still Shows

Automobiles are more than machines that move us from one place to another. At their best, they are works of art.

The lines, curves, and proportions of a well-made car carry the same intention as brushstrokes on a canvas. They reflect the time in which they were created—what people valued, what they imagined, and how carefully they worked.

Older designs, in particular, reveal a devotion to craftsmanship. Attention to detail wasn’t optional; it was expected. That care lingers long after the engine stops running.

Perhaps that’s why these objects still inspire us. They remind us that when something is made thoughtfully, it invites us to treat it thoughtfully in return.

The Camera Matters Less Than the Moment It’s Pointed Toward

The camera matters less than the moment it’s pointed toward.

Seeing has always mattered more than the tool.

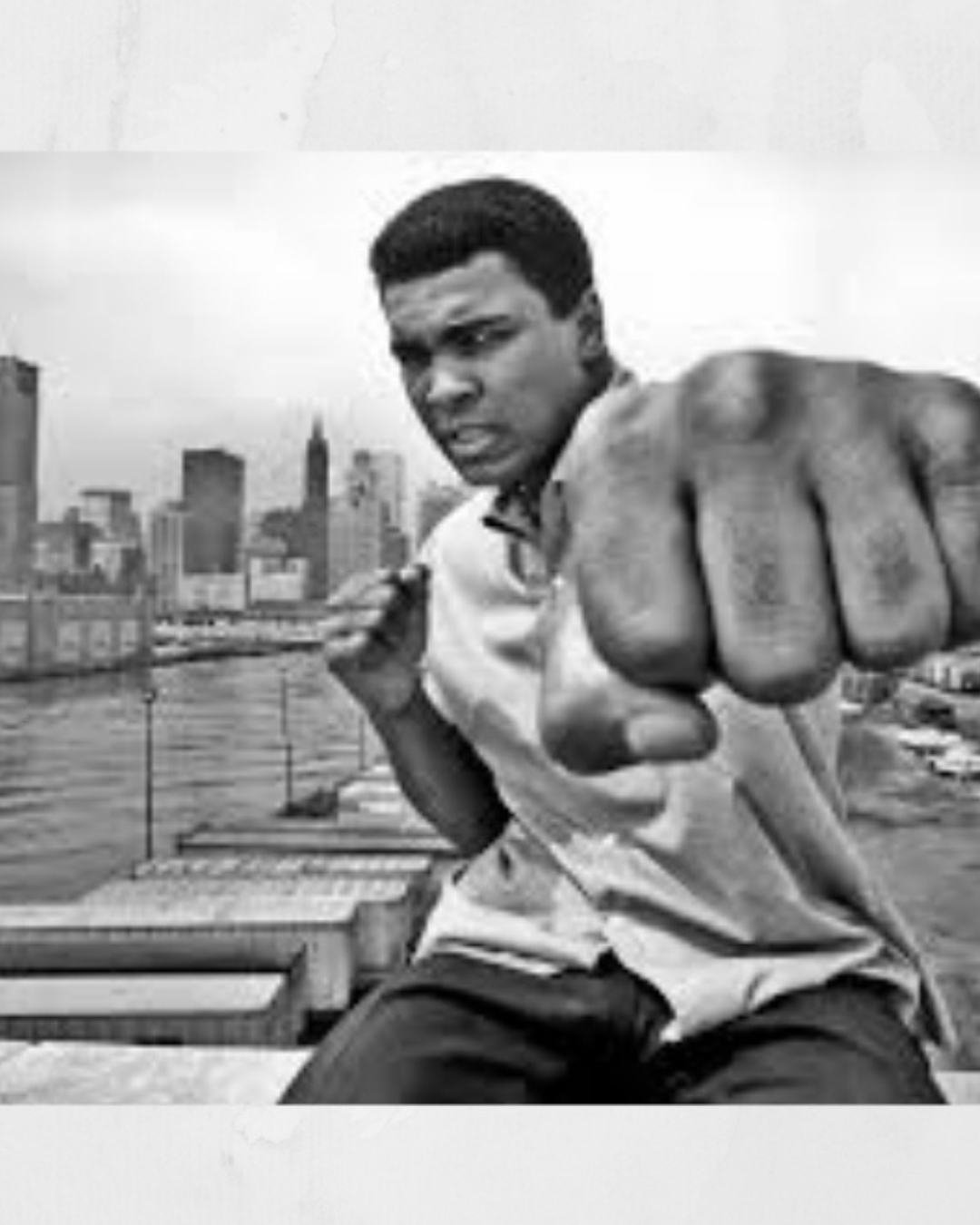

The World Looks Different in Black and White →

Without color, the eye slows down.

What remains is shape, light, and attention.

Black and white does not simplify the world. It removes the noise that keeps us from noticing it.

Faces feel closer.

Expressions linger longer.

What we read in an image comes less from the scene itself and more from what we bring to it.

Monochrome changes how we see, not by adding meaning, but by asking us to look again. And sometimes, looking again is enough.

Photo Essay or Telescope — Or Both? →

A camera on a tripod, fitted with a long lens, can feel like a telescope.

It watches from a distance. It scans before it chooses.

The telescope gathers information.

The photograph decides.

When the shutter closes, one moment is selected over countless others.

Everything before it.

Everything after it.

Everything that happened just outside the frame.

A photo essay doesn’t claim to show the whole event.

It offers a single point of attention.

What we see is not the moment itself, but a decision made within it.

Not what happened, but what was noticed.

Sociality →

Sociality is a survival response to evolutionary pressures.

Photo essays find you rather than you finding them.

Read moreYou Only Photograph the Effect of the Wind →

Winds arrive, sometimes gently, sometimes with force, and then they pass.

What remains is never the wind itself, only what it touched.

Scripture tries to name this mystery:

And after the fire came a still small voice.

(1 Kings 19:11–12)

Sometimes a photograph works the same way.

It becomes a sacred record—not of the force itself, but of its aftermath.

You never see the wind.

You see the tree bent slightly off-center.

The water disturbed.

The moment changed.

The image is not the event.

It is the evidence

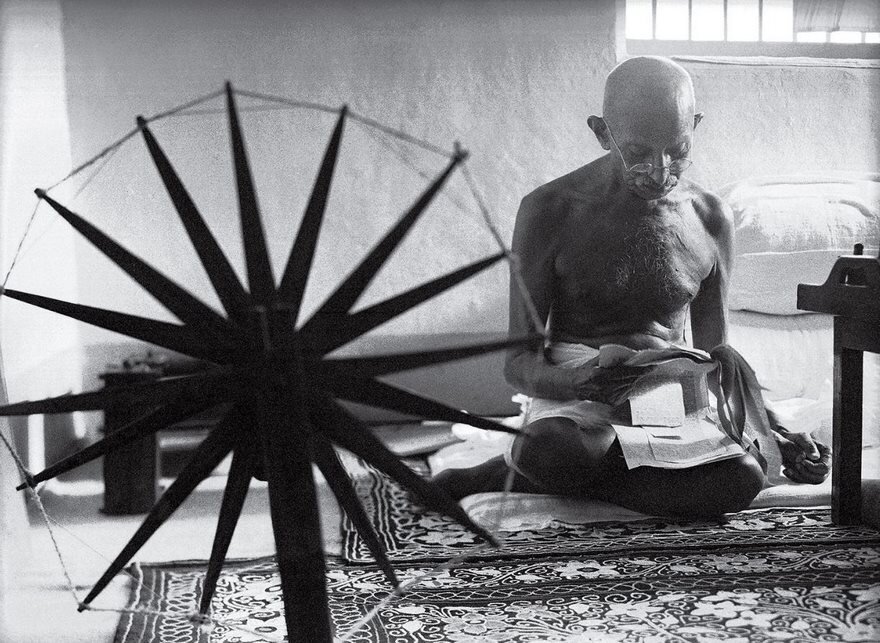

Gandhi and the Spinning Wheel: When a Photograph Becomes Philosophy →

In 1946, photographer Margaret Bourke-White captured Mahatma Gandhi seated beside a spinning wheel, the charkha. The image is quiet, spare, and deliberate.

The photograph does not document an event. It reveals a philosophy.

For Gandhi, the spinning wheel symbolized self-reliance and resistance without violence. He believed the revival of hand-spinning and hand-weaving could restore both economic dignity and moral independence to the masses. What began as a personal practice during his imprisonment at Yeravda Prison became a central emblem of India’s struggle for freedom.

The power of the photograph lies in its restraint. There is no spectacle. No crowd. Only a man, a tool, and the discipline of repetition.

This is why the photo works as an essay.

It doesn’t argue.

It embodies.

Decades later, the image still communicates what words struggle to hold: that resistance can be patient, purposeful, and profoundly human.

The Photo Is the Essay: Why Some Images Outlast Words →

On the morning of June 5, 1989, photographer Jeff Widener stood on a sixth-floor balcony of the Beijing Hotel, documenting the aftermath of the Chinese government’s violent crackdown in Tiananmen Square.

As a column of tanks moved along Chang’an Avenue, a lone man stepped into their path. Widener continued shooting, unsure whether he was witnessing an act of courage—or the man’s final moments. The tanks slowed. Then stopped.

The man climbed onto one of the vehicles, spoke briefly with the crew, and resumed his place in front of the column. Eventually, he was pulled away by bystanders. His identity and fate remain unknown.

Others photographed the scene, but Widener’s image was transmitted over the Associated Press wire and appeared on front pages around the world. In time, the photograph became known simply as Tank Man.

Decades later, the image endures not because we know who the man was, but because we don’t. His anonymity allows the photograph to speak beyond its moment—to stand for resistance, vulnerability, and the quiet force of a single human presence confronting power.

This is why photographs matter.

They do not explain.

They endure.

A Camera Is a Time Machine →

A camera doesn’t just record what was in front of it.

It carries moments forward.

When we look at a photograph, we aren’t simply seeing the past—we’re encountering it from where we stand now. Time has shifted us. Context has changed. What once felt ordinary may now feel essential.

Photographs don’t explain our lives, but they remind us of what mattered enough to be noticed. They hold moments still long enough for meaning to catch up.

In that way, a photo essay isn’t about nostalgia.

It’s about presence—past and present meeting in a single frame.

What the Window Held →

We don’t always stop for the moments that stay with us.

This image was captured in passing—seen through a window, moving quickly, already gone by the time it registered. The falls were frozen, suspended in mid-descent, holding their shape against the season.

Some things don’t ask for our full attention. They arrive briefly, insist on being noticed, and remain long after we’ve moved on.

Winter, Reduced to Essentials

Winter has a way of simplifying the world.

Sound softens. Color fades. What remains is light, shadow, and the quiet persistence of standing still long enough to notice both.

I’m drawn to moments like this—not because they explain anything, but because they don’t ask to.

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

BY ROBERT FROST

Whose woods these are, I think I know.

His house is in the village, though.

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

On the darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark, and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

Ducks, Geese, Coots, and Gulls at Oquirrh Lake →

On Oquirrh Lake, in the southwest corner of the Salt Lake Valley, winter settles in layers. Sometimes the ice rests just beneath the surface of the water. Along the edges, it rises above it.

Ducks gather in large groups, floating calmly where the water remains open. Others move toward the shoreline, appearing for a moment as if they are walking on water, until their feet find the ice and they step forward without hesitation.

The geese don’t always arrive at the same time as the ducks. On days like this, the ducks dominate the lake. The coots, however, seem to be constantly present throughout the year, moving quietly through the same familiar space.

Ducks’ feet aren’t insulated with fat the way the rest of their bodies are. Instead, their circulation minimizes heat loss. By the time blood reaches their feet, it is already cooled, reducing the transfer of warmth to the ice and water below. It’s a simple adaptation, but an effective one.

They don’t seem bothered by the cold beneath them. They simply adjust and remain.

Breathe in the Amazing and live life. →

Life is Amazing. Of course, it is, but it is also astonishing, astounding, fabulous, fantastic, unbelievable, marvelous, miraculous, phenomenal, prodigious, stupendous, impossible, incredible, and wondrous.

Breathe in the Amazing and live life.

A River Ran Through It - An Amazing Memory

Photo by Stefano Carini